Analyzing Political Polarization: Engagement Graphs 🏛

Part one of a three in a series that breaks down my undergraduate thesis in an accessible and engaging format. Posted on the popular blog Towards Data Science.

NOTE: this was my first uninhibited, and unsupervised, exploration into computational social science. While I learned a lot from this project, it's clear that the methods and findings are not well-founded. It was, however, lots of fun! I'm leaving these posts up for posterity but, again, would not consider it close to rigorous.

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2006/1*eiNLacvtxOcNhN_DZ9E2Jw.png) American Senate voting graph. Source: Andris et al.

American Senate voting graph. Source: Andris et al.

The above network, I believe, is telling when it comes to our current political climate. Less and less are our politicians willing to work across the aisle in order to pass bi- or multi-partisan legislature. While this network from The Economist uses American Senate votes to illustrate this phenomena, partisanship is on the rise globally and is not only found in “formal politics”. Over the past 40 years, people have become less willing to be friends¹, work with², or marry³ someone with different political beliefs. This is a term referred to as homophily, and in a word means that “birds of a feather flock together.” Why is this a problem? Often political beliefs act as borders, fencing people of different classes, religions, and ethnicities in — so in the interest of a more connected, tolerant society, understanding political partisanship is huge⁴. In this 3 part series, I will argue that by using network science, unsupervised machine learning, and computational social science — we can gain a more nuanced understanding of political polarization, and when and how it occurs. Specifically, we’ll use engagement graphs and natural language processing to show that certain types of messages are used to rally a political party leader’s supporters, while others span political beliefs.

There are a few different bases to cover before we can dive in to the network science and NLP. First, we’ll clarify a few concepts surrounding what political polarization is, what it exactly is we’re measuring, and the context we’re conducting this research in. Then, we’ll need a theoretical framework. In this case, our research is rooted in the assumption that both the producer of content and the content itself affect how people behave online — and that this assumption should be observable in the social networks we build. This underpinning is the basis that guides the second and third installments, and allows us to derive some really interesting results. If you want to read the full paper, which is under review for publication in Network Science, it’s available at cameronraymond.me.

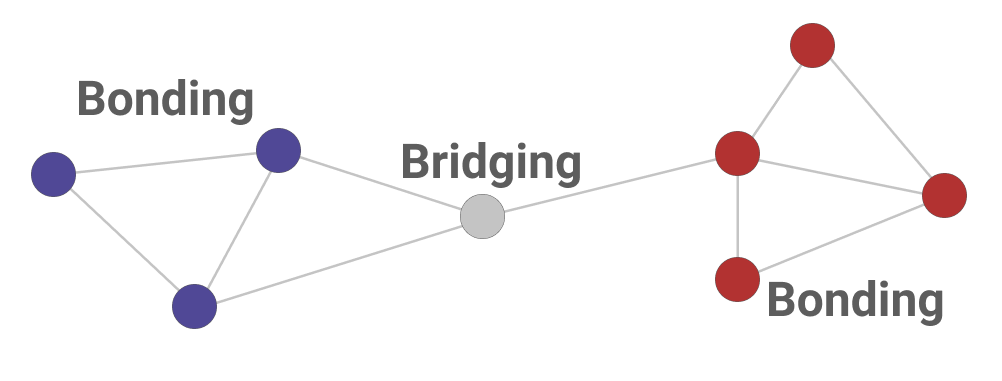

Bonding versus bridging social capital

Bonding versus bridging social capital

Political polarization is a broad term that can often refer to different phenomena in different contexts, and it is important to note that not all messages promoted by in politics will serve the same purpose. Dog whistles, micro- targeting, and persuasion games are often a part of electoral politics⁵. Some messages may be logistical in nature, informing party affiliates of campaign events; other messages may be promoted in an attempt to rally that party’s supporters; others, finally, may be an attempt to attract engagement from new, untapped demographics⁶. The last two categories are in similar to Robert Putnam’s idea of social capital, which is the concept that “social networks have value.”⁴ Here, Putnam draws the distinction between two forms of social capital: the bonding type, brings a group together – and the bridging type, which spans different demographics⁴. But how do different types of messaging affect the bridging or bonding capabilities of social media? This is important because information is likely to spread differently in each case. Bridging messages take advantage of the strength of loose ties, and spread of information diffusely. Bonding messages on the other hand concentrate the spread of information within a group. This is the question we’ll answer: are their data to support the notion that some political messages are bonding in nature, rallying members within a group, while other political messages are bridging in nature? Since Canada had a recent election in 2019, we will use the tweets of Canada’s five major, English speaking party leaders—Andrew Scheer, Elizabeth May, Jagmeet Singh, Justin Trudeau, and Maxime Bernier — and their retweets leading up to the election as our data.

Coming back to our theoretical framework, how can we build networks that allow us to analyze how Twitter users engage with both party leaders and different types of messages? This is where engagement graphs become a useful tool. An engagement graph is a type of network that has three different categories of vertices. Vertices are represented by circles in a network and refer to a thing, vertices can be people, companies, cities… the list goes on.

An example engagement graph.

An example engagement graph.

First, there are vertices in the network that produce content — in this case, these are the five political party leaders we’re looking at. Then, there are vertices that represent the content itself. In this case, each tweet we collect is its own content vertex. Finally, there are what we call general users who choose what content to engage with. These are the politically active Twitter users who decide what tweets from the party leaders they want to retweet.

Every time a party leader tweets something, we add a new content vertex and draw an edge (represented by lines connecting vertices) from that party leader to that tweet. Every time a user decides to retweet one of the party leaders’ tweets, we draw an edge from that general user to the tweet they retweeted. In this way content acts as an intermediary between the party leaders and the general users. This allows for a fine tuned analysis and acknowledges that certain users may engage with certain content producers when they produce certain forms of content, but choose not to engage with that same producer if the subject matter differs. The full engagement graph for the tweets leading up to the 2019 Canadian election is shown below, and includes the 5 party leaders; their 7,978 tweets; and 113,293 retweets across 36,450 general users. While interesting to look at, it’s impossible to make sense of, so we’re going to need some way of quantifying these relationships to see how some tweets bridged while others bonded.

Canadian political engagement graph.

Canadian political engagement graph.

This has been a lot of theory! But this article developed a robust framework, that takes into account the producers of content, the content itself and the people who engage with content. This framework is the springboard into parts 2 and 3, where we’ll do a deep dive on the data, use unsupervised topic modelling to classify tweets as different topics, and then develop two new metrics of topic centrality. These two metrics measure how important tweets of different topics were to the entire network, and to the supporters of each individual party leader. By comparing and contrasting the two, we’ll be able to gain insight on the properties of different types of messages, and finally answer whether some messages act as bridges, when others act as barriers. Thanks for sticking with me and keep an eye out for next week, when we take this framework and start applying AI and network science.

[1]: Huber, Gregory Alain, and Neil Ankur Malhotra. Dimensions of political homophily: Isolating choice homophily along political characteristics. Stanford Graduate School of Business, 2013.

[3]: Huber, Gregory A., and Neil Malhotra. “Political homophily in social relationships: Evidence from online dating behavior.” The Journal of Politics 79, no. 1 (2017): 269–283.

[4]: Putnam, Robert D. “Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital.” In Culture and politics, pp. 223–234. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2000.

[5]: Schipper, Burkhard C, & Woo, Hee. (2018). Political awareness, microtargeting of voters, and negative electoral campaigning. Microtargeting of voters, and negative electoral campaigning (september 17, 2018).